Ready to learn more?

Home » Insights » Estate Planning » Estate Planning: Navigating the Emotional Journey of Property Transfers Before Saying Goodbye

Logan Baker, JD, LL.M., MBA

Lead, Sr. Wealth Strategist

The rules for transferring property before death can be complex. Learn the basics to help avoid unexpected tax consequences.

Estate planning is more than just a legal necessity — it’s a heartfelt journey of ensuring your loved ones are cared for. As we approach the delicate topic of property transfers shortly before death, it’s essential to understand the rules that can impact your family’s future. These rules, while complex, are designed to help you make informed decisions during a challenging time.

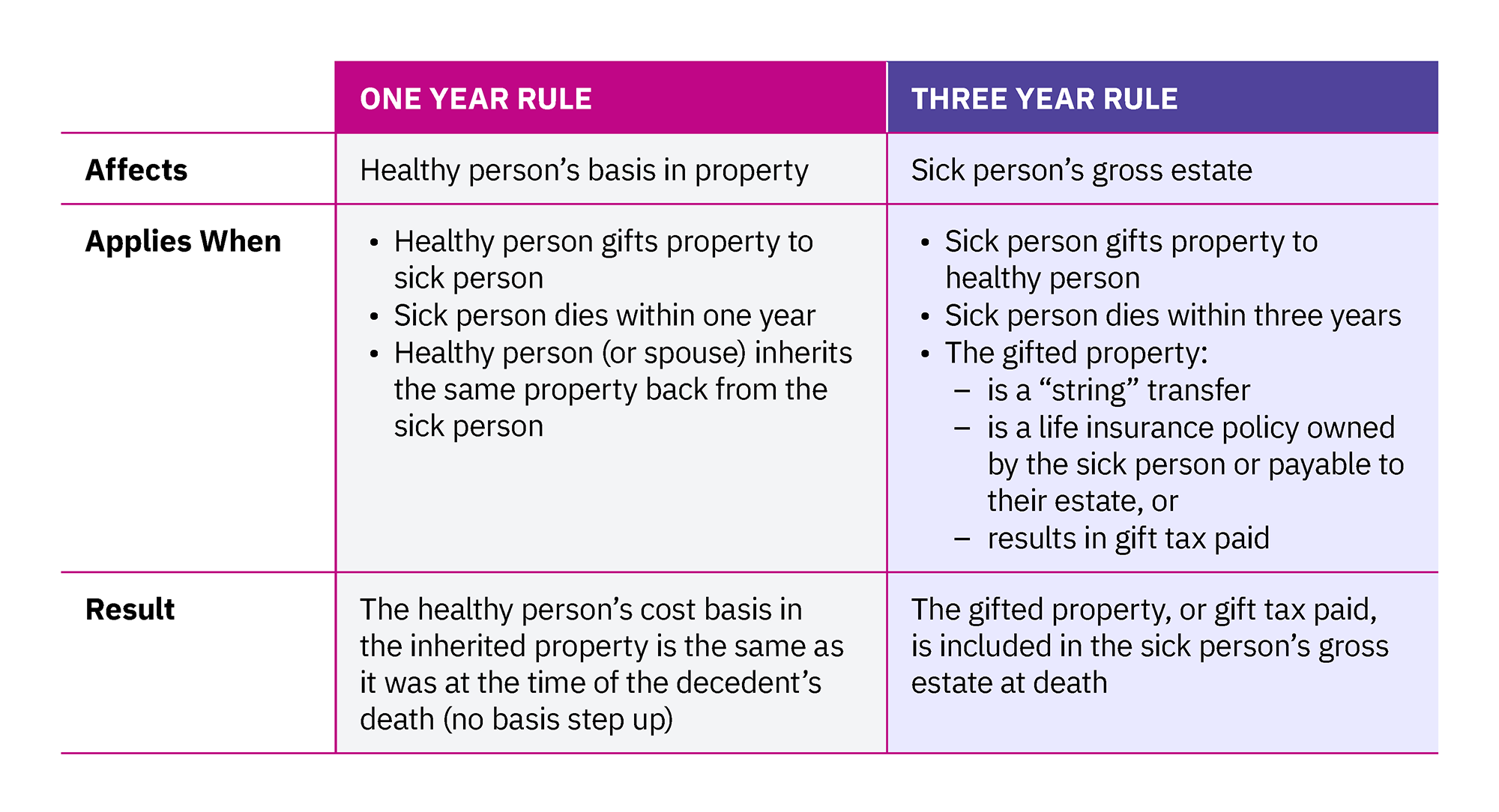

When it comes to transferring property shortly before death, two key rules from the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) come into play: the “one year rule” and the “three year rule.” Though they might seem similar, they serve different purposes and have unique implications. Additionally, there are “string rules,” guidelines for life insurance transfers, and rules for gift taxes paid. To help you navigate these waters, we’ve broken down these rules into simple, easy-to-understand explanations.

One year rule

The one year rule is designed to prevent “deathbed transfers” of those who may aim to avoid taxes. Here’s how it works:

Example: Imagine you give your mom some valuable stock, and she passes away a week later, leaving the stock back to you. Under the one year rule, you inherit the stock with the same tax basis that she had at the time of her death, not its higher value at her death. However, if your children (or any person other than you or your spouse) had inherited the property, then it would still get the basis step-up.

Three year rule

The three year rule affects certain gifts and transfers made within three years of death. Here’s a straightforward breakdown:

Example: If you transfer a life insurance policy to someone else but you pass away within three years, the policy’s value might still be included in your total estate.

String rules

The IRC has three rules, known as string rules, to prevent people from avoiding estate taxes by giving away assets but still benefiting from them. In each string rule scenario, the property will be included in the individual’s total estate value at death and cannot avoid estate taxes. Section 2036 pertains to gifts in an estate that an individual still retains in their possession, gets the use, enjoyment, or income from, or retains the power to designate who gets possession, use, enjoyment, or income. Essentially, the individual has gifted away property while keeping “strings” attached to it.

Section 2037 is similar to 2036 but the individual who gifted the property in their estate retains no immediate interest; rather, they are planning to get the gifted property back at some point in the future upon a specified event occurring. Section 2038 applies to revocable transfers of property gifted in an estate by an individual who retains the ability to change the gift or take it back.

In any of these instances, if the person who makes the “string” gift then cuts that string within three years of their death, the value of the property can be added back into their gross estate for estate tax purposes. This is the three year rule of IRC 2035.

Transfers of life insurance

While life insurance may be typically thought of as non-taxable, the death benefit of any life insurance policy is included in a decedent’s estate if it is payable to the decedent’s estate, or the decedent was the owner of the policy at the time of death according to IRC Section 2042. This rule basically led to the creation of the Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT). By placing the ownership of a life insurance policy in an ILIT and naming the ILIT as the beneficiary, it can avoid being included in the total estate value. However, if an existing policy is transferred to an ILIT within three years of the policy owner’s death, then the death benefit is included in the owner’s gross estate even though they did not own the policy at their death. This is another application of the IRC 2035 three year rule.

Gift taxes paid

Section 2035(b) requires the decedent’s estate to take money already paid to the IRS in gift tax on any gift made within three years of death and add that money back into the gross estate as part of the tax base on which estate tax will be calculated. To better understand this rule, it helps to know the difference between the tax inclusive estate tax and the tax exclusive gift tax because the rule is designed to disincentivize deathbed transfers by savvy taxpayers who understand the difference.

For example, imagine a scenario in which your parent had an estate of $20 million at death and previously used all of their lifetime estate and gift tax exemption amount. You inherit your parent’s full estate and are named executor. You pay the tax bill of $8 million (40% of $20 million) and keep the remaining $12 million. The estate tax is considered tax inclusive because the money that the estate will ultimately use to pay the estate tax bill is part of the $20 million tax base on which the estate tax is calculated.

In a second scenario, your parent gifts you $14,285,714 prior to passing away, they report the gift tax, and give the IRS a check for $5,714,286 (40% of $14,285,714). Together, the gift to you and the IRS payment total the $20 million estate and your parent dies with an estate of $0. Your parent was able to pass more on to you in the gift tax example than in the estate tax example. The gift tax is tax exclusive because it is based only on the $14,285,714 gift, not the entire $20,000,000 estate. To curtail use of such deathbed transfer strategies, the three year rule of IRC 2035(b) requires the $5,714,286 gift tax payment to be included in your parent’s gross estate. That would result in an estate tax owed of $2,285,714 (40% of $5,714,286) which, when added to the $5,714,286 gift tax already paid, equals the $8,000,000 in total transfer tax payments from the estate tax example.

Summary

Key takeaways

First of all, when it comes to your estate, plan ahead. These rules highlight the importance of early and thoughtful estate planning. Secondly, consult professionals. As noted at the beginning, IRC rules can be complicated and working with estate planning professionals could make it easier and more effective to navigate these rules and optimize your estate plan. Understanding these rules can help you make better decisions and avoid unexpected tax consequences. Contact your Mercer Advisors wealth advisor for estate planning assistance.

If you want more information about the rules for property transfers shortly before death or estate planning in general, and you’re not a Mercer Advisors client, let’s talk.

Mercer Advisors Inc. is a parent company of Mercer Global Advisors Inc. and is not involved with investment services. Mercer Global Advisors Inc. (“Mercer Advisors”) is registered as an investment advisor with the SEC. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author as of the date of publication and are subject to change. Some of the research and ratings shown in this presentation come from third parties that are not affiliated with Mercer Advisors. The information is believed to be accurate but is not guaranteed or warranted by Mercer Advisors. Content, research, tools and stock or option symbols are for educational and illustrative purposes only and do not imply a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell a particular security or to engage in any particular investment strategy. Hypothetical examples are for illustrative purposes only. Actual investor results will vary. For financial planning advice specific to your circumstances, talk to a qualified professional at Mercer Advisors.

Mercer Advisors is not a law firm and does not provide legal advice to clients. All estate planning document preparation and other legal advice is provided through select third parties unaffiliated to Mercer Advisors.