Ready to learn more?

Explore More

Logan Baker, JD, LL.M., MBA

Lead, Sr. Wealth Strategist

Understanding trust taxation requires familiarity with different rules based on the type of trust.

Not many people think about the tax implications of trusts until they become suddenly relevant, like when settling a complicated estate matter. Yet, although trust taxation can be a vexing topic that produces endless confusion, questions, mistakes, and general consternation, understanding some of the intricacies can be an important first step in preserving your wealth. This article explains the general rules of trust taxation and how those rules apply to different types of trusts.

How to answer any trust tax question

One statement will, in most cases, address any trust tax question:

Some trusts are ignored for tax purposes. If this is the case, then the trust’s income is reported on the grantor’s 1040. If a trust is not ignored for tax purposes, then the trust pays tax on income that is retained, and the beneficiary pays tax on income that is distributed. Capital gains almost always stay in the trust.

That’s private trust taxation in a nutshell. The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is the source of the rules that underlie the statement.

When are trusts disregarded for tax purposes?

If some trusts are ignored for tax purposes what are these trusts and why are they ignored? They’re known as “grantor trusts” and the circumstances under which a trust is considered a grantor trust are outlined in IRC. Trusts that aren’t grantor trusts are sometimes called “non-grantor trusts.”

If a trust is a grantor trust, then it’s disregarded for income tax purposes, and all the trust’s income, deductions, credits, and other income tax attributes are deemed to belong to the grantor.1 For tax purposes, the items are reported directly on the grantor’s Form 1040 and an income tax return typically isn’t required for the trust.

A grantor trust can allow a grantor to transfer assets out of their taxable estate while still personally paying the income tax on those assets. While paying income tax may initially sound like a bad thing, this allows the trust assets to grow tax-free for the remainder beneficiaries. The strategy can also reduce the income tax burden if (and to the extent that) the grantor is in a lower tax bracket than the trust2. Furthermore, each check that the grantor writes to the IRS removes additional funds from the grantor’s estate with no impact on the lifetime estate and gift exemption because paying one’s tax obligation isn’t considered a gift.

Another benefit of disregarded income status

Two “triggers” that cause a trust to be treated as a grantor trust are 1) the ability of the grantor to substitute trust assets for assets of equivalent value (“swap power”) and 2) the ability to apply trust income for the grantor’s benefit, including distributing income to the grantor or using income to pay for life insurance on the grantor’s life.3

If a trust is drafted to include swap power, not only is grantor trust status triggered, but the grantor can also remove and replace trust assets during their lifetime. Assets that have significantly appreciated in value since being contributed to the trust can be removed, thus bringing those assets back into the grantor’s estate and realizing a basis step-up at death. This allows the cost basis of assets inherited from a decedent to be adjusted to their fair market value at the time of the owner’s death, thus wiping out any built-in capital gains for the beneficiary. The removed assets can be replaced with cash or other assets that don’t have significant capital gain exposure.

Because a grantor trust is disregarded for income tax purposes, the removal and replacement of appreciated assets isn’t treated as a taxable sale or exchange because all the assets are considered owned by the same person—the grantor. This avoids a capital gain recognition event on the swap.

Common types of grantor trusts

Certain types of trusts that are commonly encountered in estate planning are almost always drafted as grantor trusts, and there is one very common type of trust that is always a grantor trust.

IDGTs, SLATs, and ILITs (usually)

Intentionally defective grantor trusts (IDGTs), spousal lifetime access trusts (SLATs), and irrevocable life insurance trusts (ILITs) are almost always drafted as grantor trusts. While it isn’t a requirement, and there are certainly trusts of this type that are drafted as non-grantor trusts (sometimes intentionally, sometimes not), it’s usually beneficial to draft IDGTs, SLATs, and ILITs as grantor trusts to take advantage of the tax benefits (the swap power and the ability of the grantor to pay the trust’s tax bill).

On the other hand, these trusts can be drafted as nongrantor trusts in situations where it’s preferable to treat the trust as a separate taxpayer from the grantor.

Revocable trusts (always)

Any revocable trust is always (and by definition) a grantor trust. Because the grantor retains the right to revoke the trust, change the trust, or remove assets from the trust, a revocable trust falls within several grantor trust triggering rules. When we typically describe a revocable trust, we say that the trust is not a separate taxpayer; that the grantor reports all the trust income; that the trust doesn’t file a separate tax return — all attributes of grantor trusts.

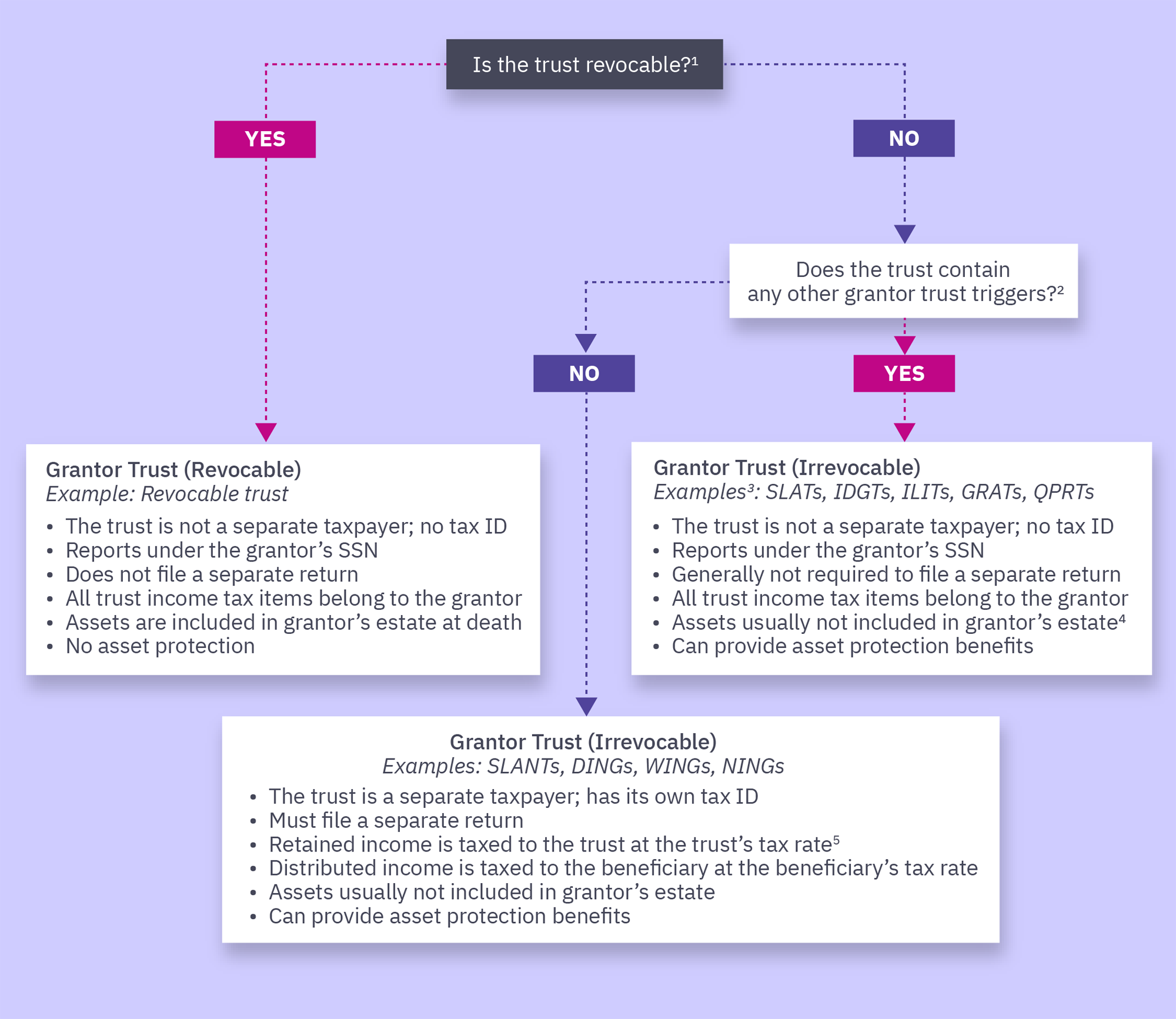

The following flow chart can be used as a quick reference for determining how a particular trust is taxed.

Taxation of non-grantor trusts

If a trust is a non-grantor trust, it’s a separate taxpayer with its own taxpayer identification number and separate income tax return. As a result, any income retained within the trust will be taxed to the trust and reported on the trust’s income tax return (Form 1041). Any income distributed to a trust beneficiary will be taxed to that beneficiary and reported on their Form 1040.

Some trusts require the trustee to distribute all the trust’s income, which will necessarily result in the income being taxed to the beneficiary. However, many trusts give the trustee discretion to retain or distribute income based on the beneficiary’s needs, allowing the trustee to make distribution decisions based primarily on what’s in the beneficiary’s best interest, but with tax considerations in mind.

Trust tax rates are compressed, and trusts pay at the top rate once they reach a very minimal income threshold. Under current 2024 law, trusts will reach the maximum 37% tax bracket at only $14,451 of income, whereas an individual taxpayer would not hit the 37% rate until they have $609,350 of income.4 To the extent that the beneficiary’s marginal tax rate is lower than the trust’s, there could be a tax benefit for the trustee to distribute income to the beneficiary rather than retaining it in trust.

Capital gains are generally allocated to principal and aren’t distributed

The tax treatment for retained income versus distributed income described above applies to ordinary income such as dividends and interest. Capital gains, however, are subject to special rules that almost always result in capital gains being allocated to the trust’s principal and therefore not available for distribution to the beneficiary. This generally isn’t detrimental from an income tax standpoint because preferential tax rates for capital gains also apply to trusts.

Be wary of trust names

Private trusts fall into three broad categories: revocable grantor trusts, irrevocable grantor trusts, and non-grantor trusts. But correctly identifying the trust category requires a careful reading of the complete trust document, including the original trust and any amendments and restatements. Names can be deceiving.

For example, what about a trust titled the Jane Smith Revocable Trust; is that a revocable trust? Maybe and maybe not. It was probably drafted as a revocable trust originally, but what if Jane passed away? Now the Jane Smith Revocable Trust is an irrevocable trust because the person who held the power to revoke it—Jane — is deceased.

If you want to know how a trust is taxed, what it’s used for, or anything else about the administration of the trust, read the entire document or, better yet, have a qualified attorney review the details.

The bottom line

Trust taxation can be a difficult topic, and several different rules can apply depending on the type of trust involved. The best approach to any trust taxation question is to remember the general rules but don’t make any assumptions about which rule applies. A trust is either disregarded for income tax purposes, in which case all income is taxed to the grantor, or the trust is a separate taxpayer that must file its own income tax return and report its own income, deductions, credits, and other tax attributes. A complete copy of the trust document, including all amendments and restatements, is necessary to answer any question about the taxation or administration of a trust. A qualified attorney or tax professional can review a trust to determine its proper tax classification and treatment.

1 IRC § 671. Grantor trusts are disregarded for income tax purposes, but not for estate and gift tax purposes. A gift to a grantor trust is still treated as a gift, and assets held in a grantor trust may be excluded from the grantor’s gross estate at death, depending on how the trust is drafted.

2 IRC § 675(4)(C), IRC § 677(a).

3 Trusts and estates pay at a top marginal rate of 37% (as of 2024), just like individuals. However, the income threshold at which for trusts and estates to reach that top rate is only $14,451.

4 IRS provides tax inflation adjustments for tax year 2024. Nov. 9, 2023.

Mercer Advisors Inc. is a parent company of Mercer Global Advisors Inc. and is not involved with investment services. Mercer Global Advisors Inc. (“Mercer Advisors”) is registered as an investment advisor with the SEC. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author as of the date of publication and are subject to change. Some of the research and ratings shown in this presentation come from third parties that are not affiliated with Mercer Advisors. The information is believed to be accurate but is not guaranteed or warranted by Mercer Advisors. Content, research, tools and stock or option symbols are for educational and illustrative purposes only and do not imply a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell a particular security or to engage in any particular investment strategy. For financial planning advice specific to your circumstances, talk to a qualified professional at Mercer Advisors.