Trade negotiations between the United States and China broke down last month, with the US responding by increasing tariffs from 10% to 25% on approximately $200 billion worth of Chinese imports. Global markets recoiled, with the S&P 500 Index returning -6.35% and the FTSE China Index returning -12.91% for the month of May (FactSet, Inc. Data as of May 31, 2019). Given all the noise around the subject, the purpose of this article is to help answer some of the more pressing questions frequently asked by clients.

First, let’s set the stage. The United States and China are the world’s two largest economies. Chinese exports make up 19% of its GDP, with 18% of all its exports going to the United States. In addition, approximately 3.4% of China’s economy is tied to US exports. In contrast, only 8% of the US GDP is tied to exports with 12.6% of those exports going to China. Moreover, 1% of US GDP is tied to US exports to China. That said, US exports to China have grown 86% over the past 10-years while exports to the rest of the world grew only 21% (US-China Business Council, State Export Report. April 2018).

What impact do tariffs have on the economy?

Tariffs are a tax. When governments wish to discourage the consumption of certain goods, they subject those goods to a special tax. Excise taxes on cigarettes, alcohol, and sugary drinks all come to mind. Similarly, tariffs increase the price of goods imported from a specific country or countries. The purpose of the tariff is to increase the price of imported goods. The increase in price has two effects: first, consumers demand less of those goods subject to the tariff; and second, consumers pay a higher price for the (reduced) quantity they do purchase. The tariff (tax) revenue paid by consumers is collected by the US Treasury. Subsequently, tariffs are paid by US consumers and reduce imports, both of which have a negative impact on economic growth.

What impact do tariffs have on stocks?

The price of any company’s stock is best defined as the present value of future expected cash flows. In English, this means profits—including dividends and retained earnings—ultimately determine stock prices. When companies expect to sell less goods (due to tariffs), the profits they can expect to earn in the future also decline. When profits decline, the value of the business—represented by shares of stock—also declines, especially for those firms with significant operations in China or other countries targeted with tariffs.

Won’t tariffs help return manufacturing jobs to the United States?

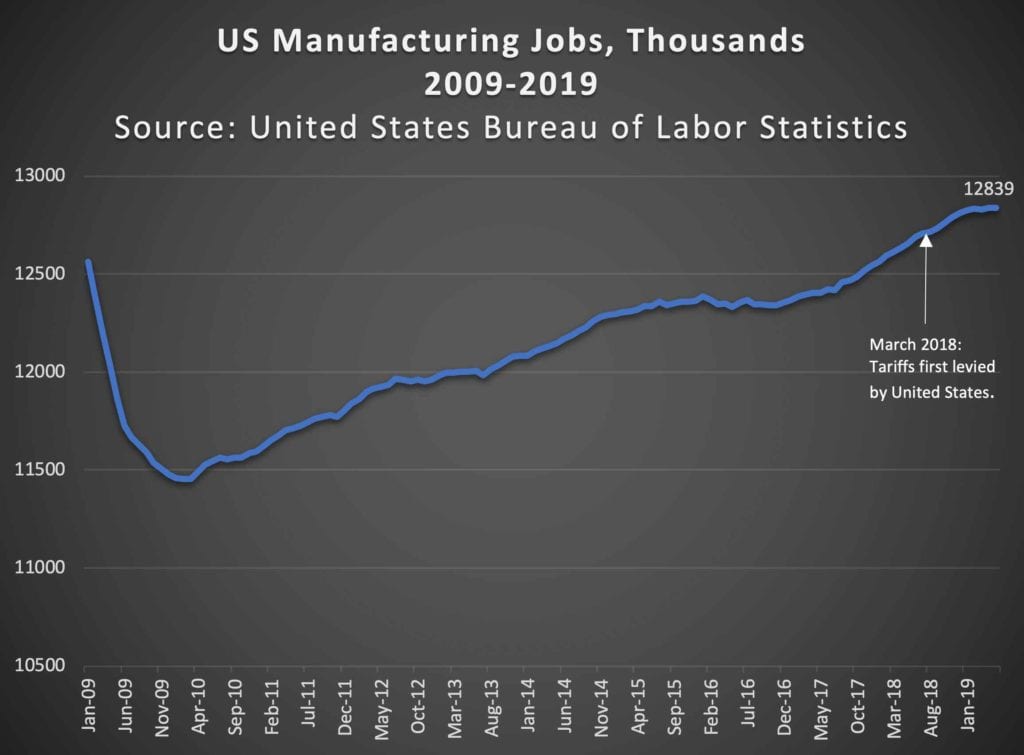

This is probably not true. Proponents of tariffs on Chinese imports highlight that, since first levied in March 2018, approximately 204,000 manufacturing jobs have been created in the United States (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.data.bls.gov). While this data point is true, it is also true that manufacturing employment in the United States has grown steadily since the aftermath of the global financial crisis. To argue this growth is due only to recently implemented tariffs would be a stretch for two reasons. First, it ignores the fact that manufacturing jobs have continued to rise since 2010. Second, it assumes that US manufacturing companies responded to US tariffs quite rapidly (within days and weeks) of when tariffs were first implemented. That seems unlikely given how long it takes for manufacturers to redesign and implement new supply chains.

Finally, if indeed a cause and effect relationship is established between recently passed US tariffs and the 204,000 in new manufacturing jobs, those jobs came at a staggering economic cost to the US economy. For example, it’s estimated that China’s retaliatory tariffs will cost US companies about $54 billion (Peterson Institute for International Economics, as quoted in USA Today, “Who gets hurt by China’s new tariffs on American Goods?”, May 13, 2019). That works out to about $265,000 per US manufacturing job; several economists from the University of Chicago and the Federal Reserve put the estimate at $820,000 per job in certain sectors (Flaaen, Hortacsu, and Tintelnot, “The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machine”, Working Paper at the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago, April 18, 2019).

Should investors be concerned about China’s current position as the world’s largest producer of Rare Earth Elements (REE)?

We don’t think so. While a disruption to REE exports might have a short-term impact on certain industries (especially technology) most economists argue the effects would be short-lived (Barrett, Eamon. “China’s Rare Earth Metals Aren’t the Trade War Weapon Beijing Makes them Out to Be”, Fortune, May 29, 2019). This assessment makes sense when we evaluate the evidence and apply some economic intuition. There are a number of REE projects underway worldwide that could quickly fill any reduction in REE exports by China (US Geological Survey as quoted in Zero Hedge “Beijing Has Reportedly Developed Plan for Rare-Earth Export Ban”, May 31, 2019). The central issue isn’t that the rest of the world doesn’t have REE deposits; it does. The issue is one of economics. At current prices, it’s relatively uneconomical for other nations—especially the US and Canada—to develop REE deposits. This is because REE export prices are heavily subsidized by China’s lax labor and environmental standards (especially relative to Western countries where environmental and labor standards are much stronger). Any move by China to implement tariffs or export bans would push up prices, making other (currently uneconomical) REE mining projects suddenly more economical to develop.

But can’t China just dump its massive holdings of US treasuries and subsequently hurt our economy?

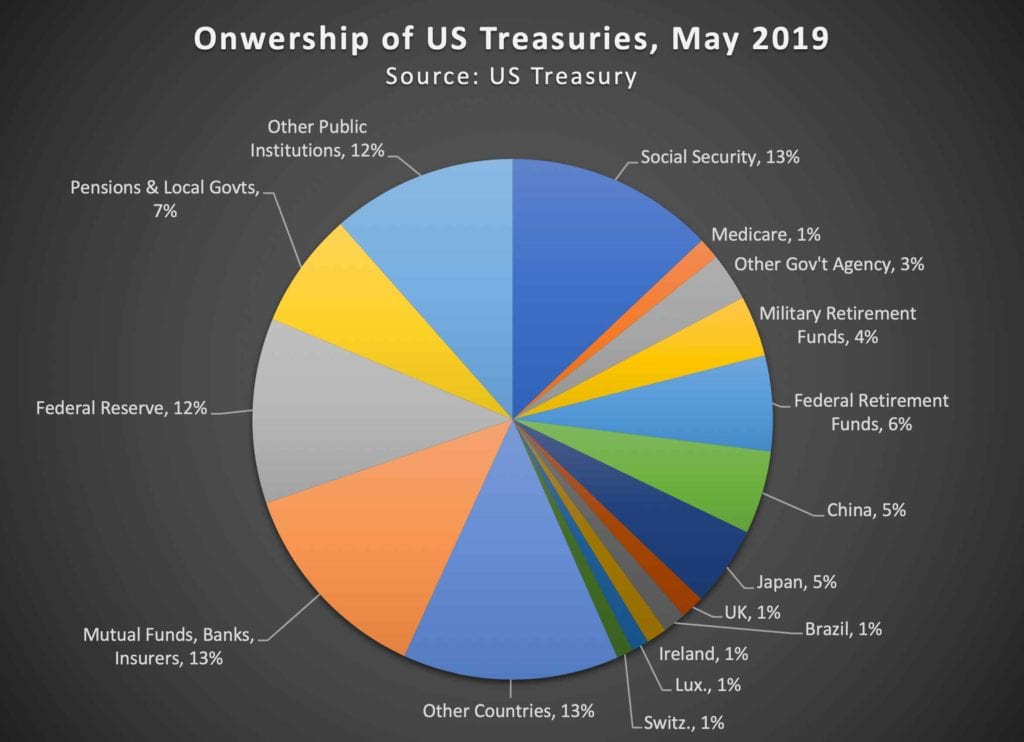

This doesn’t seem likely. It’s true that China holds about $1.12 trillion in US Treasuries, but it’s also true that there are several practical barriers to China dumping all or much of its treasury holdings on the market (US Treasury www.ticdata.treasury.gov, “Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities”, March 2019). First, doing so would likely hurt the value of their own holdings. Second, there’s nowhere else for China to reinvest their proceeds that offers the relatively high yield and low risk provided by US treasuries. Third, it’s not clear that selling all $1.12 trillion of China’s treasuries would move the market that much. There is a total of $22 trillion in US Treasury debt outstanding, and while China is the largest foreign owner of US treasuries, it actually owns only about 5% of total treasuries outstanding with over $600 billion in US Treasury securities changing hands each and every day (www.sifma.org/resources/research/us-treasury-daily-volume). Finally, China actually began slowly selling its US treasury holdings in 2014 and has already reduced its holdings of US treasuries by about $300 billion since with no noticeable impact to US interest rates.

Mercer Advisors Inc. is the parent company of Mercer Global Advisors Inc. and is not involved with investment services. Mercer Global Advisors Inc. (“Mercer Advisors”) is registered as an investment advisor with the SEC. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered, or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author as of the date of publication and are subject to change. Some of the research and ratings shown in this presentation come from third parties that are not affiliated with Mercer Advisors. The information is believed to be accurate, but is not guaranteed or warranted by Mercer Advisors. Content, research, tools, and stock or option symbols are for educational and illustrative purposes only and do not imply a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell a particular security or to engage in any particular investment strategy. For financial planning advice specific to your circumstances, talk to a qualified professional at Mercer Advisors. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Therefore, no current or prospective client should assume that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy or product made reference to directly or indirectly, will be profitable or equal to past performance levels. All investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss. Changes in investment strategies, contributions or withdrawals may materially alter the performance and results of your portfolio. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment will either be suitable or profitable for a client’s investment portfolio. Historical performance results for investment indexes and/or categories, generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges or the deduction of an investment-management fee, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results. Economic factors, market conditions, and investment strategies will affect the performance of any portfolio and there are no assurances that it will match or outperform any particular benchmark. This document may contain forward-looking statements including statements regarding our intent, belief or current expectations with respect to market conditions. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements. While due care has been used in the preparation of forecast information, actual results may vary in a materially positive or negative manner. Forecasts and hypothetical examples are subject to uncertainty and contingencies outside Mercer Advisors’ control.

Home » Insights » Investing » Putting the US-China Trade War in Context: Questions & Answers

Putting the US-China Trade War in Context: Questions & Answers

Donald Calcagni, MBA, MST, CFP®, AIF®

Chief Investment Officer

Summary

Trade negotiations between the United States and China broke down last month, with the US responding by increasing tariffs from 10% to 25% on approximately $200 billion worth of Chinese imports. Global markets recoiled, with the S&P 500 Index returning -6.35% and the FTSE China Index returning -12.91% for the month of May (FactSet, Inc. Data as of May 31, 2019). Given all the noise around the subject, the purpose of this article is to help answer some of the more pressing questions frequently asked by clients.

First, let’s set the stage. The United States and China are the world’s two largest economies. Chinese exports make up 19% of its GDP, with 18% of all its exports going to the United States. In addition, approximately 3.4% of China’s economy is tied to US exports. In contrast, only 8% of the US GDP is tied to exports with 12.6% of those exports going to China. Moreover, 1% of US GDP is tied to US exports to China. That said, US exports to China have grown 86% over the past 10-years while exports to the rest of the world grew only 21% (US-China Business Council, State Export Report. April 2018).

What impact do tariffs have on the economy?

Tariffs are a tax. When governments wish to discourage the consumption of certain goods, they subject those goods to a special tax. Excise taxes on cigarettes, alcohol, and sugary drinks all come to mind. Similarly, tariffs increase the price of goods imported from a specific country or countries. The purpose of the tariff is to increase the price of imported goods. The increase in price has two effects: first, consumers demand less of those goods subject to the tariff; and second, consumers pay a higher price for the (reduced) quantity they do purchase. The tariff (tax) revenue paid by consumers is collected by the US Treasury. Subsequently, tariffs are paid by US consumers and reduce imports, both of which have a negative impact on economic growth.

What impact do tariffs have on stocks?

The price of any company’s stock is best defined as the present value of future expected cash flows. In English, this means profits—including dividends and retained earnings—ultimately determine stock prices. When companies expect to sell less goods (due to tariffs), the profits they can expect to earn in the future also decline. When profits decline, the value of the business—represented by shares of stock—also declines, especially for those firms with significant operations in China or other countries targeted with tariffs.

Won’t tariffs help return manufacturing jobs to the United States?

This is probably not true. Proponents of tariffs on Chinese imports highlight that, since first levied in March 2018, approximately 204,000 manufacturing jobs have been created in the United States (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.data.bls.gov). While this data point is true, it is also true that manufacturing employment in the United States has grown steadily since the aftermath of the global financial crisis. To argue this growth is due only to recently implemented tariffs would be a stretch for two reasons. First, it ignores the fact that manufacturing jobs have continued to rise since 2010. Second, it assumes that US manufacturing companies responded to US tariffs quite rapidly (within days and weeks) of when tariffs were first implemented. That seems unlikely given how long it takes for manufacturers to redesign and implement new supply chains.

Finally, if indeed a cause and effect relationship is established between recently passed US tariffs and the 204,000 in new manufacturing jobs, those jobs came at a staggering economic cost to the US economy. For example, it’s estimated that China’s retaliatory tariffs will cost US companies about $54 billion (Peterson Institute for International Economics, as quoted in USA Today, “Who gets hurt by China’s new tariffs on American Goods?”, May 13, 2019). That works out to about $265,000 per US manufacturing job; several economists from the University of Chicago and the Federal Reserve put the estimate at $820,000 per job in certain sectors (Flaaen, Hortacsu, and Tintelnot, “The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machine”, Working Paper at the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago, April 18, 2019).

Should investors be concerned about China’s current position as the world’s largest producer of Rare Earth Elements (REE)?

We don’t think so. While a disruption to REE exports might have a short-term impact on certain industries (especially technology) most economists argue the effects would be short-lived (Barrett, Eamon. “China’s Rare Earth Metals Aren’t the Trade War Weapon Beijing Makes them Out to Be”, Fortune, May 29, 2019). This assessment makes sense when we evaluate the evidence and apply some economic intuition. There are a number of REE projects underway worldwide that could quickly fill any reduction in REE exports by China (US Geological Survey as quoted in Zero Hedge “Beijing Has Reportedly Developed Plan for Rare-Earth Export Ban”, May 31, 2019). The central issue isn’t that the rest of the world doesn’t have REE deposits; it does. The issue is one of economics. At current prices, it’s relatively uneconomical for other nations—especially the US and Canada—to develop REE deposits. This is because REE export prices are heavily subsidized by China’s lax labor and environmental standards (especially relative to Western countries where environmental and labor standards are much stronger). Any move by China to implement tariffs or export bans would push up prices, making other (currently uneconomical) REE mining projects suddenly more economical to develop.

But can’t China just dump its massive holdings of US treasuries and subsequently hurt our economy?

This doesn’t seem likely. It’s true that China holds about $1.12 trillion in US Treasuries, but it’s also true that there are several practical barriers to China dumping all or much of its treasury holdings on the market (US Treasury www.ticdata.treasury.gov, “Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities”, March 2019). First, doing so would likely hurt the value of their own holdings. Second, there’s nowhere else for China to reinvest their proceeds that offers the relatively high yield and low risk provided by US treasuries. Third, it’s not clear that selling all $1.12 trillion of China’s treasuries would move the market that much. There is a total of $22 trillion in US Treasury debt outstanding, and while China is the largest foreign owner of US treasuries, it actually owns only about 5% of total treasuries outstanding with over $600 billion in US Treasury securities changing hands each and every day (www.sifma.org/resources/research/us-treasury-daily-volume). Finally, China actually began slowly selling its US treasury holdings in 2014 and has already reduced its holdings of US treasuries by about $300 billion since with no noticeable impact to US interest rates.

Help Meet Portfolio Objectives with Factor Investing

Beyond Fees: What to Consider When Looking for an Advisor

Crypto and Bitcoin ETF Frequently Asked Questions